The New England colonists of the 17th and 18th centuries were English people, in English colonies, so their colonial flags were based on English flags

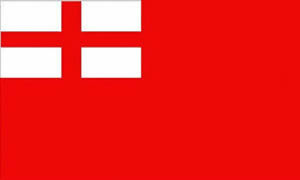

The English Flag

When the New England colonies were started, England was a kingdom, ruled by a king. Before the English Civil War (1649-1660) the King effectively “owned” the country. His flag, the flag England, was a white field with the red cross of St. George.

In contrast to England, the flag used by the King of Scotland was the cross of St. Andrew.

The English Naval Ensign before 1707

Often the flags flown by ships, known as “ensigns,” or “jacks” are variations of the country’s flag. (An ensign is flown on the main mast; a jack is flown on the bow of the ship, but we will skip the niceties of where and how and who can fly a jack. It’s not a part of this article.) From about 1600 to 1707 the English Navy ships used a Naval Ensign which was a highly visible red flag with a canton in the upper left containing the King’s Colors, to wit: the red cross of St. George.

The Massachusetts Bay Colony was formed when this English Naval Ensign was the common flag available on both English Navy and merchants ships and also in overseas colonies. Thus, when the Massachusetts Bay Colony was started in New England in 1630, this English Navel Ensign became the first flag flown on official occasions by the Colony.

Virginia, and the other English colonies, as they were formed, generally used the English Naval Ensign with — the cross of St. George — as their flag.

The Massachusetts Bay Colony Flag (Used 1636 to about 1686)

Started in 1630, the Massachusetts Bay Colony originally used the 1630 English Naval Ensign. However, a religious problem arose. The Massachusetts Bay Colony was the home of thousands of religious dissenters who came over to the New World to make get away from the Catholic Church and the Church of England. The ministers condemned the traditional “idols” of the the Catholic Church and the Church of England. In 1636, in a sermon in the Massachusetts Bay Colony, Roger Williams (before he was banished and fled to Rhode Island) fastened on the cross of St. George as an “idol” and condemned the use of the St George’s cross in the colony’s flag.

The Governor of the Colony, John Endicott, ordered the Standard Bearers of the Colony (many towns in the Colony had an official named the Standard Bearer) to remove the St. George’s Cross from their flags. Before this was done, however, the Great and General Court of the Colony decreed that Endicott’s order changing the flag “exceeded the lymits of his calling”, removed him from office, and forbid him holding any public office for one year. However, being composed of practical politicians, The Great and General Court of the Colony gave the Standard Bearers permission to devise any kind of flag they wanted. Without exception, the Standard Bearers removed the crosses from their flags.

From Endicott’s of 1636 order until about 50 years later, the unofficial flag of Massachusetts Bay was red with an blank white canton. By the late 1600’s, in New England they weren’t quite so sure that the King’s personal official flag of St. George was un-Christian, and the St. George’s cross again began to appear on flags. This solved the bland style of a barren white canton, and showed loyalty to the person of the King of England.

The (English) Union Flag

After the 1707 reunion of England and Scotland, and the subsequent change in the “King’s Colors”, the English Royal Navy used a Union Jack which was a red flag with a canton in the upper left with the King’s “unified” flag.

The Union Jack was associated with English Navy ships. As to English-owed merchant ships, in 1674 a royal proclamation had ordered English merchant ships to use the English flag of the day, the plain white flag with the red cross of St. George. Although presently much ignored the 1674 regulation never has been cancelled, so some English ships still occasionally fly the plain white flag with the cross of St. George.

New England Ships’ Ensigns

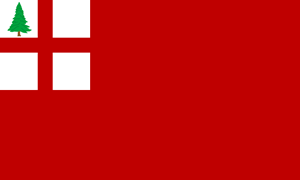

By the time the Union Jack was used by English Navy ships, the pine tree had become a core symbol of New England. The pine tree indicated not only a prime export (lumber) but also the nature of the New World. The tree started appearing on local coinage, and eventually on the flags used on merchant ships the colonists built and sailed on merchant voyages to various places in the New World as well as to Europe. Sometimes New England ships used a plain white flag with a green tree of some sort shown on it, commonly a pine tree. The New England merchants and ship captains wanted their ships in port to be clearly understood as ships sailing to/from New England. In a busy port, or in a port looking for New England fish, lumber, or rum, this was an advantage.

Instead of the plain white flag with a green tree, the more substantial ship owners of New England (with their larger ships) tended to use a variation of the Union Jack. The variation substituted a green tree for the Union Flag in the upper left white canton of the flag used by English Navy ships.

At the same time, by the late 1600’s-early 1700’s, in New England they weren’t quite so sure that the King’s cross of St. George was un-Christian, and the St. George’s cross again began to reappear in the white canton on flags.

A combination of the “King’s” cross of St. George and a pine tree eventually evolved. In a 1686 manuscript, Insignia Navalia by Lt. Gradon, an illustration of the “New England Jack” appears, showing it as a plain white flag with a red St. George’s Cross but with an Oak tree in the extreme upper left. Other documents from approximately this time period show the ship’s flags of ships of the New England colonies as being a flag with a white canton in which there was both the red St. George’s Cross and a green tree (usually pine or oak) in the extreme upper left of the canton.

By the French and Indian War (1756 – 1763) the ensign shown on the left (with the red St. George’s Cross and a green tree in the white canton) was the one most frequently flown by the ships of Rhode Island and the Massachusetts Bay Colony. Those two colonies dominated trade to and from the English New England colonies. Thus, by the time just preceding the American Revolution the flag identified by many with New England as a region was that ship flag.

When the Revolution came, the Massachusetts colony in 1775 declared its official Massachusetts Navy flag to be this naval ensign (the one first above). About the same time, George Washington’s military secretary, Colonel Joseph Reed, proposed that all American ships fly a red flag with a plain white canton with only one green pine tree in it (the second one above), so that all American ships could recognize one another. His proposal was not adopted.

Sons of Liberty Flags

The Sons of Liberty originally used a flag of 9 vertical stripes to represent the unity of the New England colonies that corresponded regularly with each other regarding measures to be taken regarding the English Stamp Act.

The history of a flag identifying the Sons of Liberty flag began in 1765, when protests of the duties and taxes and stamps required by Parliament began in the colonies. The Sons of Liberty took their name from a debate on the Stamp Act in Parliament in 1765. Members of Parliament included several prominent Members supportive of the American view that the tax was improper, William Pitt (the Elder), Charles James Fox, and Edmund Burk. During the debate, Charles Townshend, speaking in support of the Stamp Tax Act, spoke of the American colonists as being “children planted by our care, nourished up by our indulgence…and protected by our arms.” Isaac Barre, member of Parliament and friend of the American colonists, countered with a severe reprimand in which he spoke favorably of the Americans as “these Sons of Liberty.”

In Massachusetts, after a particular protest of the Stamp Act was held under a particular Elm tree in Boston, known thereafter as “the Liberty Tree,” a group known as the Sons of Liberty was formed. They met regularly under the tree. The English Army cut the tree down. The Boston people erected a pole and flew the nine-striped “Sons of Liberty” flag from it.

Among other things to protest the Stamp Act, nine colonies sent delegates to their “Stamp Act Congress” They petitioned the King and Parliament; the Act was repealed in 1766. The flag of nine red and white stripes that represented these “Sons of Liberty” became known in England as the “Rebellious Stripes.”

After the Stamp Act was repealed by the English Parliament, the Sons of Liberty erected a Liberty Pole in New York City to celebrate the repeal of the Stamp Act. There was a long-running skirmish over these Liberty Poles with the British troops stationed there (the most notable engagement being the Battle of Golden Hill on January 19, 1770). As poles were alternately erected by Patriots and cut down by troops, violent outbreaks over it raged intermittently from 1766 until the Patriots gained control of New York City government in April 1775. The last liberty pole was cut down by occupying British troops on October 28, 1776.

After the successful effort to repeal the Stamp Act, the nine- striped flag was modified to 13 horizontal stripes to represent the unity of all the colonies. That 13-striped flag became the one enshrined in our popular culture. Among other things, it was used as a United States merchant ship ensign during the American Revolution.

The Continental Colors

On January 1st, 1776, General George Washington ordered the hoisting of a “Union Flag in compliment to the United Colonies” on a 76 foot tall pole on a hill in Somerville, just outside of Boston. The flag he was talking about is known to us today as “the Continental Colors”. It was a British naval red ensign with the red field defaced by white stripes, making a field of 13 red and white stripes.

There is some conjecture that the stripes of the Sons of Liberty flag may have inspired the stripes on the Continental Colors, but there is no documentary evidence of this.

The Continental Colors flag, with its apparent combination of the British Union flag — the flag of British unity — with the Sons of Liberty Flag, sent a clear message to England that the colonists regarded their fight as one to recover their proper rights as Englishmen, not necessarily a fight meant for separation from governance by England’s king and parliament. Indeed, in Boston, when the English general in charge saw the Union Flag added to what appeared to be a Sons of Liberty flag, he first decided it meant the American troops were surrendering. He sent a note to General Washington asking why the American troops in the trenches were not laying down their arms and returning to camp to prepare for a formal surrender of their positions on Bunker Hill!

The Continental Colors were used at various times during the Revolutionary War, especially before Congress adopted the official Stars and Stripes in June 1777. For example, the Continental Colors were:

- Flown over a fort the Americans captured in the Bahamas in March, 1776.

- Flown by the American schooner Royal Savage at Lake Champlain between August and October 1776.

- Flown by the American Navy ship Andrea Doria when it entered the harbor at St. Eustatius on November 16, 1776. In the 18th century St. Eustatius was the most important Dutch island in the Caribbean. The island sold arms and ammunition to anyone willing to pay and one the few ways for the rebellious American colonies to obtain weapons. The good commercial relationship between Sint Eustatius and the United States resulted in the famous “First Salute”, when Commander Johannes de Graeff of Sint Eustatius decided to return the salute fire of the visiting Andrew Doria by firing the cannons of Fort Oranje. The United States gave the answering salute great publicity because the eleven gun salute was the first international acknowledgment of the independence of the United States.

The Continental Colors officially passed from existence on June 14, 1777 when the Stars and Stripes were born, however there are a few documented war-time uses of it after that date.

Gadsden Flag, the First Naval Jack (“Don’t Tread on Me”)

In 1754, during the French and Indian War, Franklin published his now-famous woodcut of a snake cut into eight sections. It represented the English colonies then existing, with New England joined together as the head and South Carolina as the tail, following their order along the coast. Under the snake was the message “Join, or Die”. This was the first political cartoon published in an American newspaper.

As the American Revolution grew closer, the snake began to see more use as a symbol of the colonies. In 1774, Paul Revere added it to the title of his paper, The Massachusetts Spy, as a snake joined to fight a British dragon. In December 1775, Benjamin Franklin published an essay in the Pennsylvania Journal under the pseudonym American Guesser in which he suggested that the rattlesnake was a good symbol for the American spirit:

I recollected that her eye excelled in brightness, that of any other animal, and that she has no eye-lids—She may therefore be esteemed an emblem of vigilance.—She never begins an attack, nor, when once engaged, ever surrenders: She is therefore an emblem of magnanimity and true courage.—As if anxious to prevent all pretensions of quarreling with her, the weapons with which nature has furnished her, she conceals in the roof of her mouth, so that, to those who are unacquainted with her, she appears to be a most defenseless animal; and even when those weapons are shewn and extended for her defense, they appear weak and contemptible; but their wounds however small, are decisive and fatal:—Conscious of this, she never wounds till she has generously given notice, even to her enemy, and cautioned him against the danger of treading on her.—Was I wrong, Sir, in thinking this a strong picture of the temper and conduct of America?

In the autumn of 1775, the United States Navy was established to intercept incoming British ships carrying war supplies to the British troops in the colonies. To aid in this, the Second Continental Congress authorized the mustering of five companies of Marines to accompany the Navy on their first mission. The first Marines that enlisted were from Philadelphia. This first United States Marine unit carried drums painted yellow, depicting a coiled rattlesnake with thirteen rattles, and the motto “Don’t Tread On Me.”

At the Congress, Continental Army Colonel Christopher Gadsden was representing his home state of South Carolina. He was one of three members of the Marine Committee who were outfitting the first naval mission.

Before the departure of that first mission, the newly appointed commander-in-chief of the Navy, Gadsden and Congress chose a Rhode Island man, Esek Hopkins, as the commander-in-chief of the Navy. Colonel Gadsden felt it was especially important for the new commander-in-chief of the Navy to have a distinctive personal standard. Therefore, Gadsden designed, had produced, and personally presented to Hopkins a flag to be used as the personal standard of the new commander-in-chief of the Navy.

Because Gadsden also presented a copy of this flag to his home state legislature, a description of the flag is recorded in the South Carolina legislative journals. That description is the reason the Gadsden Flag, the First Naval Jack (“Don’t Tread on Me”), is generally accepted to be used as the personal standard of the commander of the United States Navy.

“Col. Gadsden presented to the Congress an elegant standard, such as is to be used by the commander in chief of the American navy; being a yellow field, with a lively representation of a rattle-snake in the middle, in the attitude of going to strike, and these words underneath, “Don’t Tread on Me!”

It is not recorded whether Gadsden took his inspiration for his yellow flag from the Marines’ drums, or from a similar yellow “Don’t Tread on Me” flag common in the three southernmost colonies.

Hopkins apparently used the flag presented to him as his personal standard, but he designed a different flag for use as the fleet’s battle flag. It used the symbol of a snake and the slogan, which he placed on the Sons of Liberty Flag. This battle flag was used as both an ensign (a flag flown on a ship’s mast) and as a jack (a flag flown on the ship’s bow or bowsprit). Hopkins ordered his ship commanders that when Hopkins raised the battleflag, all ships were to immediately attack the enemy according to a previously arranged battle formation plan. This red and white striped flag (shown above) has been in use in the United States Navy since the Revolutionary War; and it is referred to in Navy’s regulations as the “First Navy Jack.”

The above shown design of the “First Navy Jack” is that found in two primary sources. The first one is Hopkins first set of fleet signals using flags between the ships. In the fall of 1775, as the first ships of the Continental Navy readied in the Delaware River, Commodore Esek Hopkins instructed that the signal for attack in battle would be flying “the striped Jack and Ensign at their proper places.” The second source is a color plate in Admiral Preble’s book showing essentially the same “Don’t Tread Upon Me” flag used as a Navy Ensign. [Admiral George H. Preble, History of the Flag of the United States (1880).]

Since 1777, the U.S. Navy has used the Union Jack (a flag replicating the canton i.e. white stars on a blue field of the U.S. Flag). It is ordered flown by all Navy of ships, under a Naval Regulation that the “The Union Jack” is to be flown from the jackstaff by all U.S. naval vessels, from 8 a.m. to sunset while the ship is at anchor. [* A jackstaff is a small vertical spar (pole) in the bow of a ship, on which “jacks”, not the country’s flag, are flown].

Naval Regulations have ordered the First Navy Jack to be used instead of the Union Jack on special occasions. For example, the First Navy Jack was ordered to be flown instead of the Union Jack during the entire years of 1975 and 1976, as a recognition of the United States Bicentennial. As another example, in 1977 the Secretary of the Navy specified that the ship with the longest total period of active service must display the First Navy Jack, and that regulation continues in force to the present day. The latest example of a Naval Regulation requiring the First Naval Jack is the following, still in effect.

After the terrorist attack on 9/11/2001, the Secretary of Navy, On May 22, 2002 directed that the First Navy Jack (The “Don’t Tread on Me” Flag) is to be displayed by Navy ships in port during the War on Terrorism.

SECNAVINST 10520.6

N09B1

31 May 2002

SECNAV INSTRUCTION 10520.6

From: Secretary of the Navy

To: All Ships and Stations …[except Marine Corps units not having Navy personnel attached]

Subj: DISPLAY OF THE FIRST NAVY JACK DURING THE GLOBAL WAR ON TERRORISM

Ref: (a) U. S. Navy Regulations, 1990

1. Purpose. To provide for the display of the first navy Jack on board all U. S. Navy ships during the Global War on Terrorism.

2. Discussion. As the first ships of the Continental Navy readied in the Delaware River during the fall of 1775, Commodore Esek Hopkins issued a set of fleet signals. His signal for the “whole Fleet to Engage” the enemy provided for the “strip’d Jack and Ensign at their proper places.” Thus, from the very beginning of our Navy, the Jack has been used on board American warships. The first navy Jack was a flag consisting of 13 horizontal alternating red and white stripes bearing diagonally across them a rattlesnake in a moving position with the motto “Don’t Tread On Me.” The temporary substitution of this Jack represents an historic reminder of the nation’s and Navy’s origin and will to persevere and triumph.

2. Action. The first navy jack will be displayed on board all U. S. Navy ships in lieu of the Union Jack, in accordance with sections 1259 and 1264 of reference (a). The display of the first Navy Jack is an authorized exception to section 1258 of reference (a). Ships and craft of the Navy authorized to fly the first Navy Jack will receive an issue of four flags per ship through a special distribution.

George Rogers Clark Flag

In the Revolution, military units often had different flags or no flags. Stripes were a defining feature of American flags even before the Revolution, and many military banners used by Americans featured stripes of differing colors. Records in all the colonies describe red and green flags similar to the one on the left.

In the Revolution, military units often had different flags or no flags. Stripes were a defining feature of American flags even before the Revolution, and many military banners used by Americans featured stripes of differing colors. Records in all the colonies describe red and green flags similar to the one on the left.

George Rogers Clark is credited (perhaps mistakenly) by some as using a similar red and green banner in February 1779, when he led 172 men, nearly half of which were French volunteers, from Kaskaskia, Indiana to attack the British force holding a fort at Vincennes, Indiana. They marched the 240 miles through flooded country, often shoulder high in water, sending out hunting parties for food and sleeping on the bare ground. It required 17 days to make what was normally a five or six day trip in the summer. On reaching the English fort, they surprised Vincennes. Clark ordered that a dozen flags he had with him be marched behind a slight rise to convince the British that there were 600 men rather than under 200. As a group of men with their flag completed their march behind the rise and disappear into the forest, they would quickly run hidden back to the starting point to make another march behind the rise. Back and forth they went, appearing to the observing British as a huge attacking force assembling. The Americans opened rifle fire on the fort with such accuracy that the British were prevented from opening their gunports. On the morning of the third day, the British surrendered the fort and thereby control of their other posts in the previously French dominated area of what became our Northwest Territory. It is reported that when the formal surrender of the fort took place, the English commander asked Clark “Where are all your men?”; Clark replied “They are here before you”; and the English commander turned aside with tears in his eyes. The British never regained control of these posts, and the American claims in the old Northwest served as the basis of the cession of these lands to the United States at the Treaty of Paris in 1783.

Franklin or Serapis or Paul Jones Flag

John Paul Jones was the United State’s first well-known naval fighter in the American Revolutionary War. His actions in British waters during the Revolution earned him an international reputation which persists to this day. Read more about his attacks on ships near England.

John Paul Jones was the United State’s first well-known naval fighter in the American Revolutionary War. His actions in British waters during the Revolution earned him an international reputation which persists to this day. Read more about his attacks on ships near England.

The “John Paul Jones flag” was entered into Dutch records to help Jones avoid charges of piracy when he captured the Serapis under an “unknown flag.” Here’s the story.

In 1777 John Paul Jones was creating so much havoc on the high seas with his raids on the British Merchant Marine and coastal villages that the Admiralty issued orders to have him hung as a pirate if he could be captured. The reason given for the order was a legalistic one — he did not fly the flag of any recognized nation. Although Congress had just adopted a flag, news of it had not yet reached Europe or its Ambassador, Benjamin Franklin. While Franklin pondered possible solutions to this problem, the Dutch Ambassador, acting for his government, asked for a description of the United States Flag. As far as Mr. Franklin knew, no national flag existed. Nevertheless, he gave the Dutch visitor a description of what we now call the “Franklin or Serapis Flag.” This description was sent to the Dutch Fleet, along with the orders that it be recognized on the high seas. Shortly afterwards, the Ambassador of the two Sicily’s came to call, making the same request. He also received a description of the flag, and forwarded similar orders to his country’s fleet. Mr. Franklin, then apparently, had a flag, such as he had imagined, made and sent to Jones so that it could be flown at his ships’ masthead. By doing this, he could avoid being hung as a pirate by England.

The next year, during a great battle with the English ship Serapis, Jones ship – Bonhomme Richard – was sinking and the English captain asked if Jones wanted to surrender. According to the later recollection of his First Lieutenant, Jones replied: “I have not yet begun to fight!”

The Bonhomme Richard was so badly damaged that it sank with its colors flying, but by then Jones had won the battle and had transferred his crew to the Serapis. Jones put into the Dutch port of Texel for refitting of Serapis. The British authorities in the Netherlands demanded Jones be arrested as a pirate since he flew “no known flag.” The Dutch replied that they would consult their archives. A few days later when they replied to the British that they had evidence in their files that the flag used on the “Serapis” was a recognized flag and that Jones would be allowed to refit. A painting of this flag was made as a part of the legal defense of Jones.

First Official U.S. Flag

On Saturday, June 14, 1777, the business of the Continental Congress was recorded as primarily to do with the Marine Committee. The record shows, among other transactions, that the Navy wanted directions regarding the fleet in Delaware in case of British attack and that John Paul Jones was appointed as Captain of the ship Ranger. In between those two items, without a word of comment or explanation, is the Resolve that “the Flag of the united states be 13 stripes alternate red and white, that the Union be 13 stars white in a blue field representing a new constellation.”

On Saturday, June 14, 1777, the business of the Continental Congress was recorded as primarily to do with the Marine Committee. The record shows, among other transactions, that the Navy wanted directions regarding the fleet in Delaware in case of British attack and that John Paul Jones was appointed as Captain of the ship Ranger. In between those two items, without a word of comment or explanation, is the Resolve that “the Flag of the united states be 13 stripes alternate red and white, that the Union be 13 stars white in a blue field representing a new constellation.”

Marine Committeeman Francis Hopkinson designed the first stars and stripes flag. Although the size or placement of the blue field was not specified in the Resolve, all productions of the flag have followed the general arrangement of these Continental Colors, with a blue canton.

It is known that Hopkinson intended the stars to signify a new entry into the constellation of nations. But the original design of Hopkinson is not known. His stars may have been in a ring or in rows. His exact design of the stars is not known, and the placement of the stars in the canton varied considerably during the first 50 or so years of the United States. At the end of the war, in 1783, the flag drawn by Pierre L’Enfant, as part of his drawings of the new Capitol city he was planning, had the 13 stars in a circle.