he Medal of Honor is the highest award for valor in action against an enemy force which can be bestowed upon an individual serving in the Armed Services of the United States. Generally presented to its recipient by the President of the United States of America in the name of Congress, it is often called the Congressional Medal of Honor. Following is, first, the official citation, and, then, second, a summary of Bucklyn’s actions.

The President of the United States

in the name of Congress

takes pleasure in presenting the

Medal of Honor

to JOHN K BUCKLYN

Rank and Organization: First Lieutenant, Battery E, 1st Rhode Island Light Artillery.

Place and Date: At Chancellorsville, Va., 3 May 1863.

Entered Service At: Rhode Island.

Born: 15 March 1834, Foster Creek, R.I.

Date of Issue: 13 July 1899.

Citation:

Though himself wounded, gallantly fought his section of the battery under a fierce fire from the enemy until his ammunition was all expended, many of the cannoneers and most of the horses killed or wounded, and the enemy within 25 yards of the guns, when, disabling one piece, he brought off the other in safety.

Joseph Bucklin Society’s summary of what happened on 3 May 1863, at Chancellorsville, VA

Rhode Island’s 1st Regiment Light Artillery’s Battery E had three sections, each with two cannons. Bucklyn was in charge of one section.

“Lieutenant Bucklyn, although one of the sections had been engaged less than his, was ordered by Captain Randolph to return up the road in face of the enemy and check the advance. Lieutenant Bucklyn remarked, ‘whoever goes up there will not live to return.’ Captain Randolph replied, ‘I think likely they will not ; I must have some one who will stay.’ Lieutenant Bucklyn called for volunteers and every man of his section volunteered although believing he was going to certain death.”

An entire Mississippi infantry brigade stormed the line where Bucklyn’s section of Battery E was positioned. . Bucklyn ordered that the two cannons of his section fire canister shells (shells that were like giant shotgun shells in their action). Half of the men in the section were killed and most of the others wounded from the Confederate direct fire into their position.

Twice Bucklyn had horses shot from under him, as he moved rapidly among the cannons to direct their fire. As he mounted the third horse, the horse was hit with a Confederate artillery shell, and a piece of shrapnel went into Bucklyn’s left lung, filling the lung with blood and making him unable to breath effectively. Yet still Bucklyn fought Battery E both bravely and effectively.

As the Confederate infantry brigade closed on his position, and with no Union infantry supporting Battery E, he successfully maintained maximum firepower from his section of the battery. He moved the two cannon to various positions even though most of the horses were dead. The two cannons were fought by him to the last possible moment, as described in the commendation for the Congressional Medal of Honor described at the top of this page. At the last moment possible he had the remaining horses remove one of the cannons to a point of safety behind Union lines, and he remained to disable the other before leaving the field.

Stephen Usler, of Warwick, RI, is writing a biography of John Knight Bucklyn, and has said the following regarding the treatment of Bucklin’s wounds at Chancellorsville:

Bucklyn “was taken to a hospital in Georgetown. It was the same hospital described by Louisa May Alcott in her “Hospital Sketches, written while she was a nurse, although she and Bucklyn were not there at the same time. Bucklyn’s description of the place and her description corroborate that the conditions were pretty bad.

A soldier of Bucklyn’s unit, named Slocum, fed Bucklyn milk with a spoon and a surgeon dressed his wounds. Bucklyn determined that he was not going to stay at the hospital in Georgetown. Slocum put Bucklyn in a boxcar, on a stretcher on top of some coffins of Union soldiers being shipped home. There was a deserter hiding out in the boxcar and he threw Bucklyn off the stretcher and used it to sleep on himself while Bucklyn spent the journey on the floor of the boxcar.

There was nobody helping him. He ended up in a train station in New York all by himself and described having to beat off pickpockets. About six or eight weeks later, he was back at the front with his battery.”

Bucklin voluntarily returned to military service with his unit after only about two months for recovery. When Bucklin returned to to service, his demonstrated bravery and intelligence earned him the job of Assistant Aide of the Adjutant-General (AAAGen) on the staff of Colonel Thompkins. In that job, Buckyn had the duty of getting into the thick of battle in the front lines, reorganizing units to fight as battle casualties broke down the effectiveness of a fighting unit or eliminated the unit’s commanding officers, reorganizing and recombining remnants of units, and issuing new battle orders on the spot.

During the bloody battle of Shenandoah, in recognition of extreme bravery and effectiveness in battle, he was promoted in the field to the rank of brevet captain on the 19th of October, 1864, “For gallant and meritorious and ofttimes distinguished service before Richmond and in the Shenandoah Valley.”

During the latter part of the Civil War, Bucklyn as a Lieutenant (brevet rank of captain) was moved to replace the commander of Battery E, even though on paper the former commander who was moved to a general staff position. Because Bucklyn did not have an actual Congressional commission of a rank needed to command an entire battery, the former Captain remained nominally The Battery E commander on the tables of organization of the artillery.

Rhode Island’s Battery E fought continuously in battles from the start to the end of the Civil War. At Gettysburg, Battery E was stationed first at Cemetery Ridge, and later at the Peach Orchard, scenes of perhaps the most intense fighting of the Civil War, his command was exemplary. The appreciation his men had for Bucklyn as their commander on that bloody battleground was illustrated in 1886, when a monument was erected on the Gettysburg battlefield, to mark where Battery E had fought. After the service of dedication, several of the soldiers asked for permission, and were granted permission, to chisel at the bottom of the monument for Battery E’s position the additional words: “Lt. J. K. Bucklyn Commanding”.

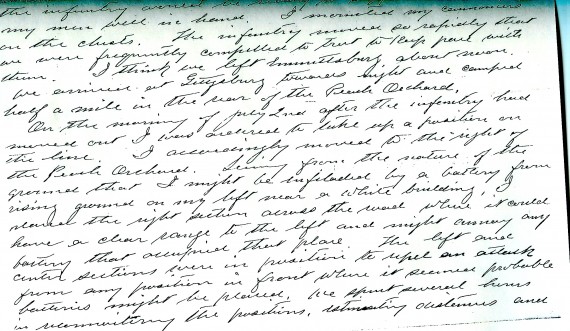

We have on file a copy of John K. Bucklyn’s entire speech to the Soldiers and Sailors Historical Society, in which he described the battle and what he did. It is one of those items that reposes in our pile of papers for which we do not have funds to put into electronic format for you to read. We wish someone would volunteer to transcribe his handwriting into a typed document, so we can make it readable and searchable for today’s researchers, and place it on our website in full. Click on the thumbnail to enlarge it to see what you would be transcribing into an electronic format (such as Word or WordPerfect). If you don’t want to donate your time, you could donate about $60 to have one of our researchers do the necessary work.